Reading Csikszentmihalyi on a family Bank Holiday in sunny France, I was reminded of the tyranny of progress and performance.

Reading Csikszentmihalyi on a family Bank Holiday in sunny France, I was reminded of the tyranny of progress and performance.

Not that it was Csikszentmihalyi’s fault. We’d been talking with friends the night before going away about learning musical instruments and the merits of lessons and regular practice.

Now I firmly believe that the best way to improve at anything is to practice regularly – the action of water on a stone is gradual, but inexorable. I have also learnt that the best way to practice anything regularly is to integrate it your daily routine. The problem is there are only so many hours in the day. What to do? More, less often?

I remember from my time working in advertising in France in the 1990s that people have predictable daily and weekly habits. But we do not generally form monthly habits and signally fail to form fortnightly habits. This gave rise to the unspoken rule, never buy an an Ad next to a monthly or worse a fortnightly TV show – they never pull in a regular audience and generally fail. Even if they are well liked once, people forget to tune in ever again. We are creatures of routine.

So where does that leave us with practice, hobbies and busy lives. My conclusion is the only practical options are dedicating daily or weekly slots. My daily slots are all pretty much full: kids, work, kids, eat, dishwasher, potter briefly, bed.

The brief evening pottering – which recently was when I walked our ageing dog – is the remaining ‘purposeable’ slot. But a few minutes spinning the wheels, albeit aimlessly, seems a very small concession to relaxation. It’d take something ‘light’ and ‘fun’ to fit in edgeways in that small nook in a way that didn’t feel like a chore.

The ukulele used to be that thing. And for nearly a year I played five songs nearly every night and went from hopeless and tuneless to strumming comparatively competently. Then the dog got incontinent and the habit got broken. So I could go back to the uke. But here’s where the tyranny of progress kicks in. Our friends feel I should have lessons, improve, look to play publicly or at least in private duets and preferably drop the four strings and migrate to a proper six string guitar.

Phew. Where’s the eudaimonia in all that – the pressure to rapidly improve my skill to meet the challenge of musical excellence feels most unappealing. I said ‘no thanks’. They looked at me like I was mad – what’s the point of strumming the same five songs and never playing them with, or for, someone. Where’s the progress, where’s the performance. The point though – I think – is I quite enjoy it as a personal exercise for me, for ten minutes at night. The simple challenge I set myself is met by my rudimentary and very slowly improving strumming skill: producing modest, low-impact, private, musical ‘flow’.

Separately, on hols I was congratulated twice on my French – one woman said “Vous parlez très très bien Monsieur”. Another asked me if I was a French teacher in England.

I had given up keeping up my French. I’d given up listening to ‘intermediate French’ audio magazines I subscribed to when I first came back from France. There were no opportunities to match my once reasonable skill with any worthwhile challenge at home. Talking about nothing much in French, just to speak French, seemed pretty pointless. And over time I felt myself going backwards which made matters worse.

But ‘flow’ in French has returned. Family holidays now provide me the perfect opportunity to navigate the modest but important challenges of travelling, accommodating, feeding and entertaining my little family. And they seem quietly impressed and genuinely grateful for my efforts. Now I have a stage on which to perform, some modest (daily?) investment in progress and improvement suddenly seems worthwhile – I’ll be looking at what the web has to offer for ‘intermediate French’ these days.

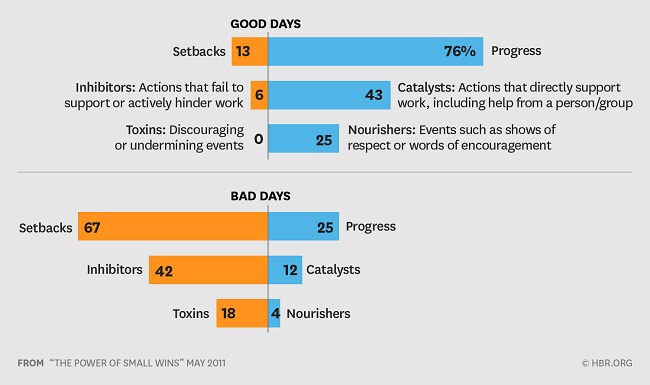

‘Flow’, progress and performance are closely intertwined, so much Csikszentmihalyi amply demonstrates. But I conclude the recipe and mix aren’t always the same. There are things we do well, some we may do very well and many we could do better. I believe good day-to-day ‘flow’ lies in accepting that not everything we do has to be excelled at. Sometimes the only audience that matters is ourselves.