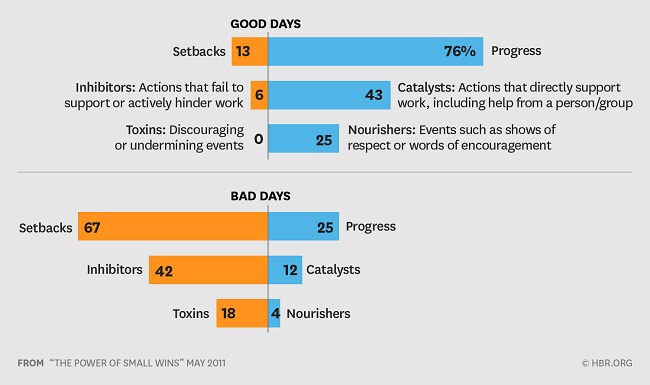

An interesting discovery from ‘Learned optimism‘ is that rumination is the optimist’s worst enemy… Chewing the cud leads to pessimism and inaction.

One thing I’ve learned at work down the years is: ‘if in doubt, do something’.

Armed with this new insight I’m even more sure taking and helping others take action – sometimes any action – is my best defence against mine and their pessimism.

And this reminded me to look up Hannah Arendt the great 20th century philosopher, who I seemed to remember was big on action too…

I was right. Here’s a boiled down extract from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“For Arendt, action constitutes the highest realization of the vita activa, via three categories which correspond to the three fundamental activities of our being-in-the-world: labor, work, and action.

Labor is judged by its ability to sustain human life, to cater to our biological needs of consumption and reproduction.

Work is judged by its ability to build and maintain a world fit for human use.

Action is judged by its ability to [manifest] the identity of the agent and to actualize our capacity for freedom.

Although Arendt considers the three activities of labor, work and action equally necessary to a complete human life, it is clear from her writings that she takes action to be the ‘differentia specifica’ of human beings.

Action distinguishes [us] from both the life of animals (who are similar to us insofar as they need to labor to sustain and reproduce themselves) and the life of the gods (with whom we share, intermittently, the activity of contemplation).”

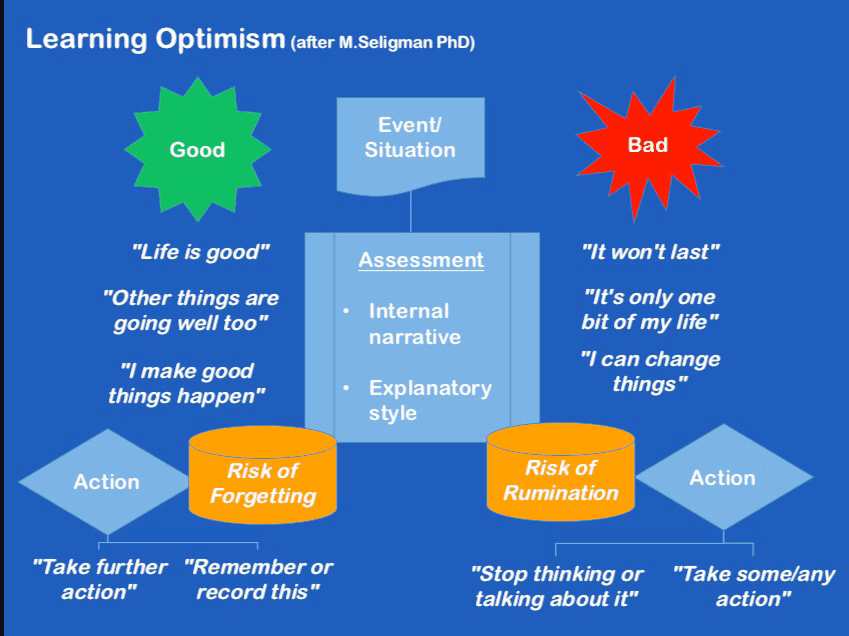

Nuff said. I made myself a little flowchart last Sunday to remind me, which still seems on the money…

In the face of setbacks, troubles and ugliness; don’t ruminate – act.

In the presence of success, progress and beauty; act – but don’t forget to contemplate too.

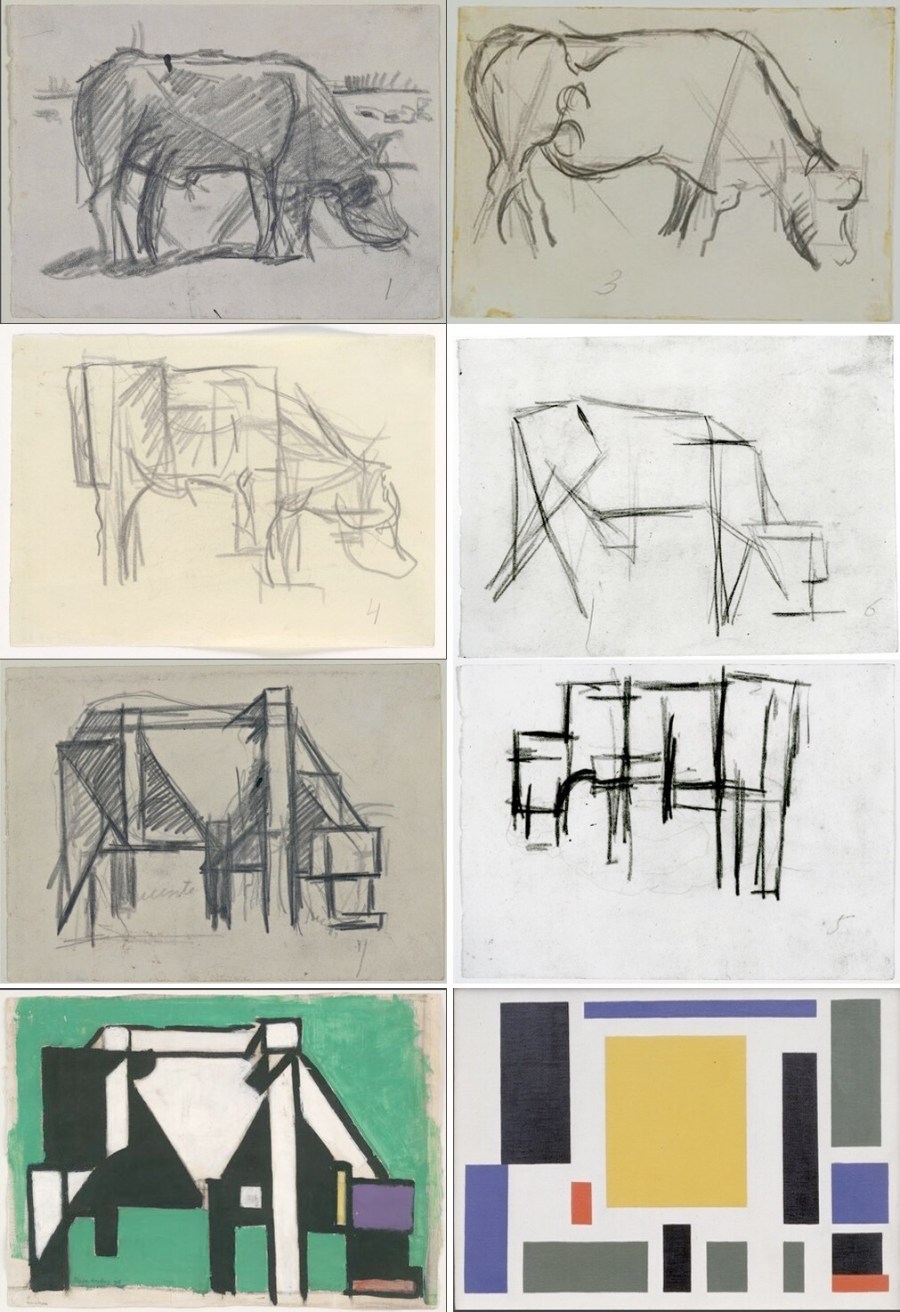

Or another way to look at it, less Theo van Doesburg:

More Franz Marc:

No more chewing the cud.