Hats off to the British Museum for combining fine photography with clear writing to explain ‘Chinese Art in Detail‘ to a beginner. That’s surely what museums are for – to blow away any cobwebs and bring their collections to life.

I learn that the hierarchy of Chinese art places calligraphy and painting at the top, closely followed by jades and bronzes – as objects of scholarly reverence and contemplation – all sitting above the decorative arts: lacquer, porcelain and silk. Sculpture was reserved for graves, temples and shrines.

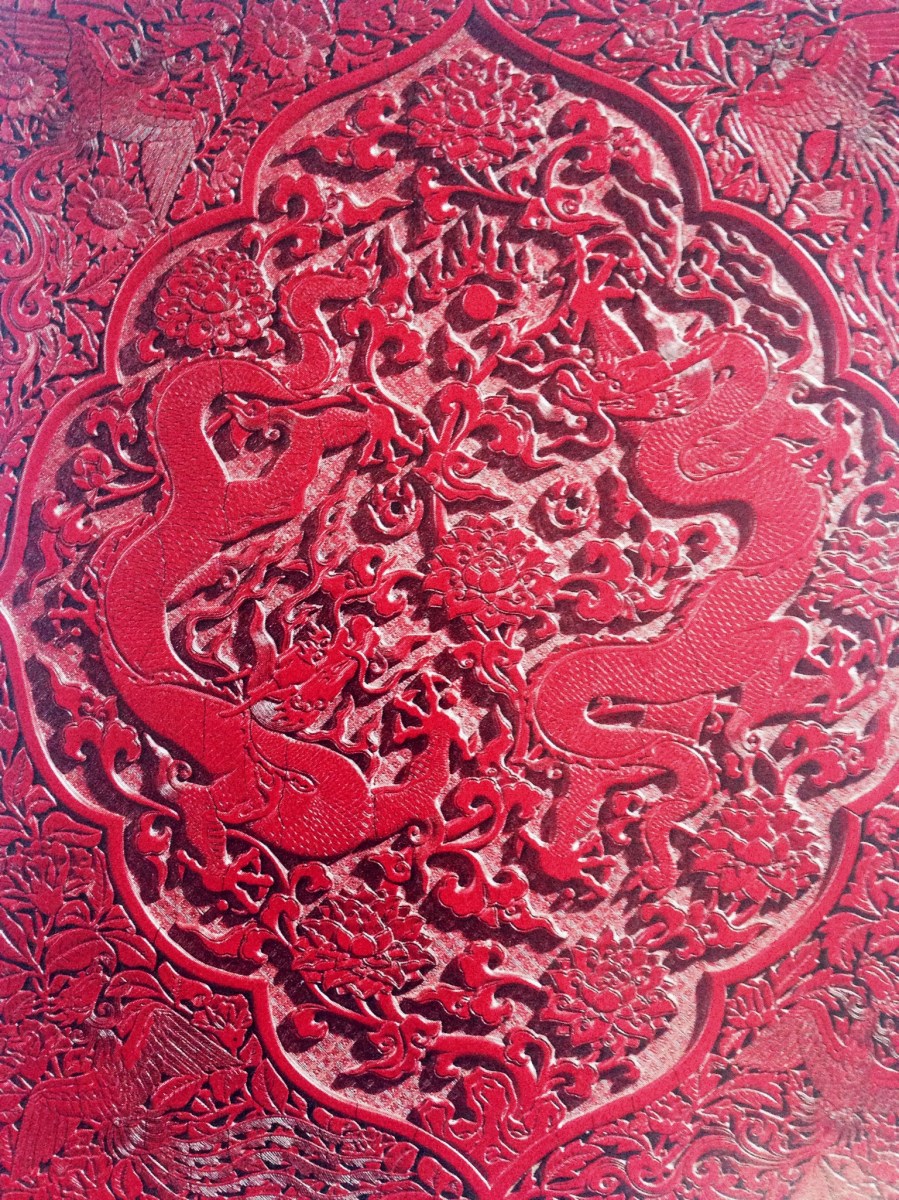

A five toed dragon reveals an imperial purpose (a toe was chipped off lacquer work if it left the emperor’s palaces) while scholars practised the ‘three excellences’ of painting, poetry and calligraphy (with incredibly intricate jade brush pots) producing mystical landscapes designed to express their cultivation.

But most remarkable is the scale and organisation of Chinese arts and crafts. Genuine mass production dates back to well before the Han Dynasty (208 BC to 220 AD) with multiple stages, many distinct craftsmen and multiple inspectors producing the highest quality lacquer and porcelain in great quantities.

Only China knew how to produce silk or fire fine cobalt blue porcelain for long periods of history. And China’s vast scale of production ensured Chinese design served and responded to the insatiable demand of the silk routes, the near East and Europe for many centuries.

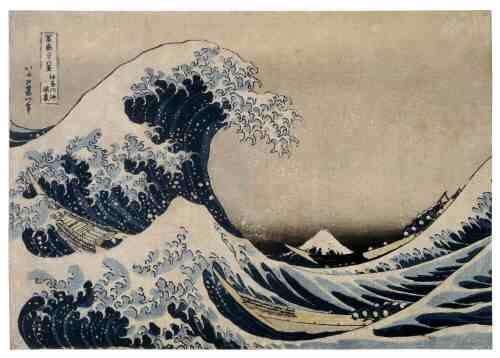

Cranes, peaches, fish, all symbolise long life and prosperity. And China’s arts and crafts often secured them for its many imperial dynasties. Bronze, jade, lacquer, porcelain, silk, scrolls, statues, woodblock prints and more – there may be no oil paintings, but the details and workmanship are amazing.

Well done to two UK public institutions of culture – a small seaside library and the unmatched British Museum – for bringing them to life from centuries past to the present day. China is as much a part of our collective past as our present and future – and this book shows its intricate art is worth a closer look.