Does seeing cruelty make us more or less likely to engage in it? Catalunya has just banned bullfights. But I saw one in Colombia nearly 20 years ago and felt I could see the nobility in it which Hemingway describes in ‘Death in the afternoon’.

Does seeing cruelty make us more or less likely to engage in it? Catalunya has just banned bullfights. But I saw one in Colombia nearly 20 years ago and felt I could see the nobility in it which Hemingway describes in ‘Death in the afternoon’.

Montaigne though thinks cruelty to animals does desensitise us:

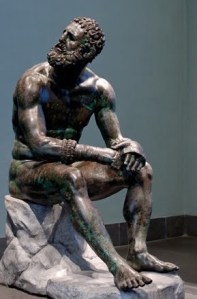

Those natures that are sanguinary towards beasts discover a natural proneness to cruelty. After they had accustomed themselves at Rome to spectacles of the slaughter of animals, they proceeded to those of the slaughter of men, of gladiators.

He also points out Karma was alive and kicking in Roman France:

The religion of our ancient Gauls maintained that souls, being eternal, never ceased to remove and shift their places from one body to another; mixing moreover with this fancy some consideration of divine justice, they said that God assigned it another body to inhabit, more or less painful, and proper for its condition:

If it had been valiant, he lodged it in the body of a lion; if voluptuous, in that of a hog; if timorous, in that of a hart or hare; if malicious, in that of a fox, and so of the rest, till having purified it by this chastisement, it again entered into the body of some other man.

But if we think animals deserve our humanity, only, to keep in check our brutality to each other, the story of Koko the Gorilla suggests they are well able to judge us too.

Koko, a 40 year old female Gorilla has mastered the American Sign Language for 2000 words. But like the Border Collie which has learnt the name of 4000 stuffed toys, it’s easy to dismiss this as trial and error ‘behaviourism’ – action for reward with nothing ‘thought’ in between.

The story told by the scientist who oversees Koko suggests differently:

“It happened by accident – someone sent a DVD about primates and I didn’t really look at it, but it was playing when I looked and saw Koko watching a graphic bushmeat scene. I hadn’t previewed it like I should have. The next day Koko picked up an insert from a newspaper and it was a supermarket ad. She held up a section full of pictures of meat and signed “Shame there.”

So simple, but so powerful as a summary of what we’re capable of. As Aristotle said we are the best and worst of animals.