Reading Neil MacGregor’s A History of the World in 100 objects, on chapter 91 I came across the concept of ‘deep time’. And deeply troubling it must have been in the 1800s; as people began to come to terms with it.

‘Deep time’, I discover, was the dawning recognition that the world was much much older than people had thought – and far less constant. Prior to ‘deep time’ the world was assumed to be capricious (hence gods) but unchanging (hence the need to pacify them).

The geneticist Steve Jones (who I’ve been fortunate to spend some time with) is quoted thus:

The biggest transformation since the Enlightenment has been a shift in our attitude to time, the feeling time is effectively infinite, both the time that’s gone and the time that’s to come. It’s worth remembering that the summit of Everest, not long ago in the context of deep time, was at the bottom of the ocean; and some of the best fossils of whales are actually found high in the Himalayas.

Deep time threw everything up in the air – origins, purpose and our place not just in the world; but in those unfathomably vast aeons of time and the unimaginably vast expanse of the universe. We went from the centre of everything to tiny, transient and trivial.

Faced with this reality I’ve often cheered myself up with the thought that bits of me were formed in stars. And I read somewhere once, we all have some molecules in us which were once in Julius Caesar and Napoleon.

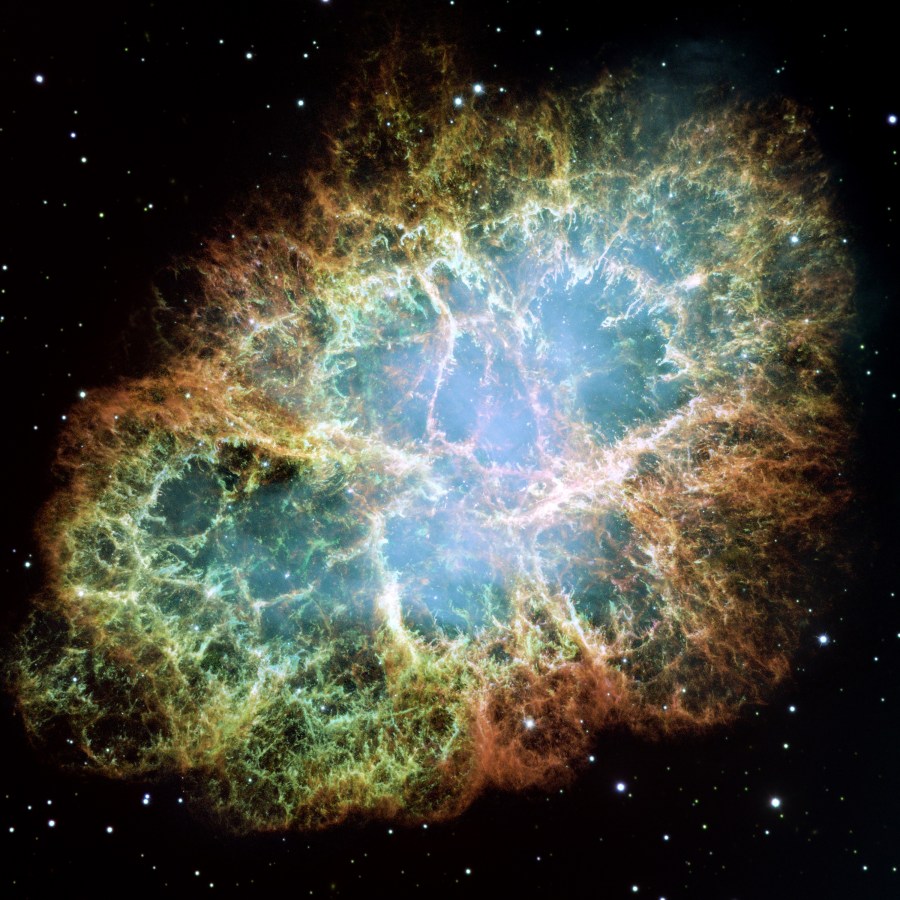

Nice therefore to read an entire feature in the New Scientist today, predicated on exactly this; the calcium atom formed in a star which is now in our bodies, the water in our blood which was once in a dinosaur etc. But the one which sparked my imagination was Stephen Battersby’s story of the iron ion formed in a supernova.

I pick up the iron nucleus’s journey here, as it is spat out from the periphery of a large black hole:

By the time our iron nucleus leaves this maelstrom, it has an energy of about 8 joules, millions of times greater than anything Earth’s Large Hadron Collider can provide. Now at about 99.9999999999999999 per cent of the speed of light. It is flung out of its native galaxy into the emptiness of intergalactic space.

As the iron nucleus wanders between galaxies, pulled this way and that by magnetic fields, its view of the universe is a strange one. At this ludicrous speed, the effects of relativity compress faint starlight from all directions into a single point dead ahead. Relativity also does strange things to time. While the nucleus is travelling, the universe around it ages by 200 million years. In another distant galaxy, Earth’s sun completes one lazy orbit of the Milky Way, dinosaurs proliferate, continents split and rejoin. But to the speeding nucleus, the whole trip takes about 10 weeks.

On the last day of its intergalactic holiday, our traveller finally approaches the Milky Way’s messy spiral. It heads towards a type G2 dwarf star, and a planet where the dinosaurs are now long dead. According to onboard time, the iron nucleus passes Pluto just 16 microseconds before it reaches Earth. When it arrives here we call it an ultra-high-energy cosmic ray.

The wispy gases of our upper atmosphere present a barrier far more challenging than anything it has encountered so far. The iron nucleus hits a nucleus of nitrogen, and the extreme energy of the collision not only obliterates both, but creates a blast of pions and muons and other subatomic particles, each with enough energy to do the same again to another nucleus, generating a shower of ionising radiation that cascades down through the atmosphere.

Some of these particle will hit an airliner, slightly increasing the radiation dose of passengers and crew. Some may help trigger the formation of water droplets in a cloud – perhaps even help spark a lightning bolt. Some will find their way into living cells, and one will tweak an animal’s genes, spurring on the slow march of evolution. But it is very likely that nobody will even notice as the atmosphere scatters the ashes of an exceptional traveller that once flirted with a black hole in the faraway Virgo Cluster.

Remarkable. When I had the chance in 2011 to spend a couple of hours with Sergei Krikalev (at that time the cosmonaut who had spent the most time in space) he told me you typically see eight to ten scintillations in your eyes every minute in orbit – little flashes in your vision – which are the cosmic rays punching through your eyeballs.

But this story of an iron nucleus would surely seem as far fetched to a person in 1815, as the things they believed then may sound to us now. A reminder that deep time for us, is only 200 years old – just a blink (or twinkle) of the eye for a cosmic ray.