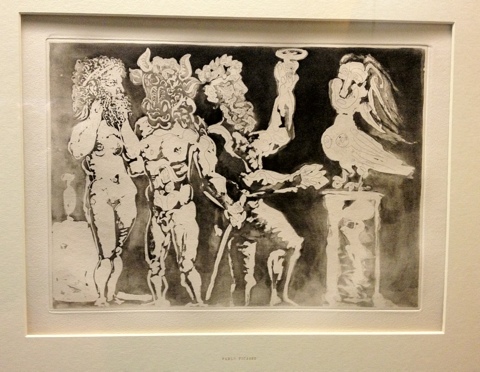

I found myself in a back room at the British Museum this week, looking at pen and ink drawings. I took a couple of photos of simple but stunning sketches by Picasso and Rembrandt.

As a child, I remember being taken to see Michelangelo’s cartoons and being mightily disappointed they weren’t a patch on Hanna-Barbera. They were instead faded brown pastels. How times change.

As a child, I remember being taken to see Michelangelo’s cartoons and being mightily disappointed they weren’t a patch on Hanna-Barbera. They were instead faded brown pastels. How times change.

Why the reappraisal – I’m much taken by Ernst Gombrich’s narrative that art of the Dark Ages was flat and naive because it was telling you something. The idea wasn’t to lose yourself in clouds, folds of garments or acres of flesh – but to ‘read’ a very simple and profound message. Almost always an illustration of virtue, sin or gospel truth, simplicity and directness were the point.

This takes me back to Aristotle’s Poetics – plot trumps spectacle and no more or less than is needed. Were I to embark on a painting I’d feel constrained to ‘represent’, to paint ‘well’ and show some technique.

Perhaps that’s not the point, the starting point for the artist is: ‘what am I wanting to say or explore?’ As with poetry, seen this way we are not ‘trapped’ by the fact that everything has been painted more beautifully by Titian, or precisely by the Dutch masters or bleakly by Caspar David Friedrich or vibrantly by Van Gogh.

The job of the artist is simply to convey what they want to say or explore. Technique and materials come second. No need therefore to hack off our beautiful – or rudimentary – artistic wings. We can all have a go.

The job of the artist is simply to convey what they want to say or explore. Technique and materials come second. No need therefore to hack off our beautiful – or rudimentary – artistic wings. We can all have a go.