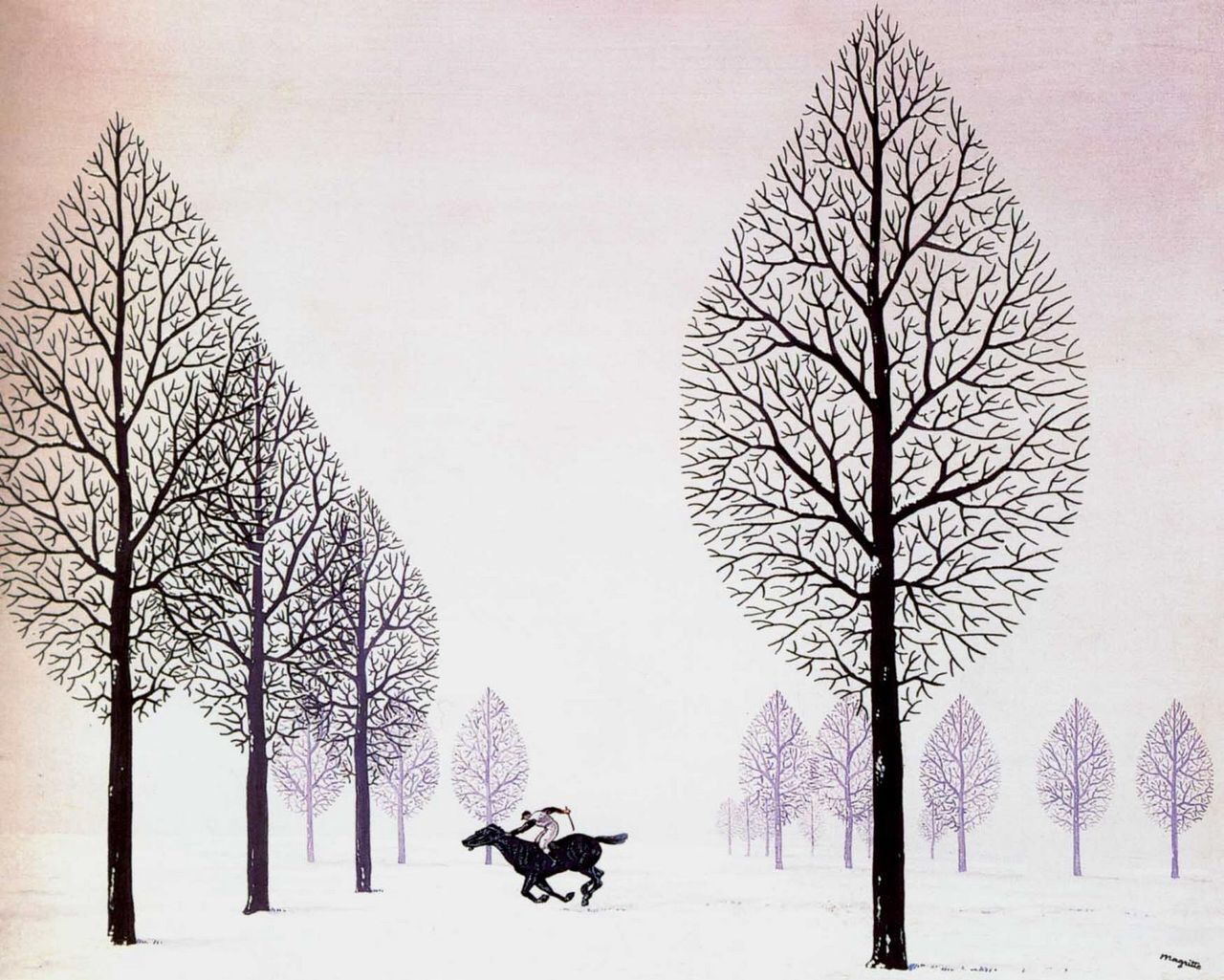

Out walking the dog, what should pop up on my podcast playlist than Keith Frankish on Philosophy Bites explaining why I was lost in thought, while the dog was 100% focused on the walk…

The difference between us is he lives in the immediate, whereas we spend a lot of our time elsewhere.

Why?

Frankish explains:

Consciousness is the distinctive feature of the human mind. Because a conscious thought is a thought about something that isn’t perceptually present. We can react to thoughts about the world detached from immediate perception.

So if we can do it, why can’t animals? Not least given we have ostensibly similar sensory apparatus and not massively dissimilar brains?

The crucial difference is we have language… Frankish’s proposal is that it is the presence of language that enables us to have conscious thought, not just conscious perception.

We don’t just use language for communicating with each other, we use language for communicating with ourselves; for stimulating ourselves in new ways, for representing the world to ourselves, for representing situations that aren’t actually real… situations that ‘might’ happen and this enables us to anticipate, to plan to prepare for eventualities that haven’t yet occurred.

He continues:

This, I think is the function of conscious thought. Conscious thought, I think, is essentially a kind of speaking to ourselves.

And by talking to ourselves we can mentally shift in time and space in ways which my trusty hound probably can’t. He’s a clever little chap – but apart from chasing bunnies and squirrels in his sleep (you can see his legs twitching as he runs them down) he’s a creature of the immediate present.

As Frankish explains:

We might say that one of the main functions of mind generally, in us and other animals, is to lock us onto the world; to make us sensitive to the world around us so we can respond quickly to changes to enable us to negotiate the world in a rapid and flexible way.

But Homo Sapiens has another trick…

The function of the conscious mind, I think is quite different. It’s not to lock us onto the world, it is to unlock us from the world – to enable us to consider alternative worlds, to consider what we would do if things weren’t as we expect them to be, to make plans for how we might change the world.

So this ability to step back from the ‘immediate’ and use language – talking to ourselves – to reflect on what is, has, might or will happen is what our unique combination of language and consciousness give us.

So far so generically interesting. But potentially even more interesting is how I’m going to try and use this insight…

Here are the mental steps:

- Most of the bad things that are happening to me in work (and there are plenty) are made worse be me running over them in my mind.

- Because I’m quite verbally dexterous I may be guilty of sharpening them in my inner dialogue to the point of exquisite pain.

- There is increasing evidence that most mental health problems contain a common ‘p’ factor of generic susceptibility.

- Treatments may vary but nearly all (bar the most serious) respond to ‘talking therapies’ which aim to change the inner dialogue.

- Mindfulness, which helps too, is all about turning off the ‘inner talking’ and returning to the moment – in effect locking back onto the world as a trusty hound would.

- Although bad things are happening to me at work (as they are for most people right now) they are still not as bad as the versions in my mind (at least not all of the time) and most of them are anticipated and haven’t actually happened yet.

- My inner voice is currently more negative and ruminative than is good for me.

- And talking to other people makes it even worse.

So what to do?

Simple – switch language, and here’s why:

- People in several different workplaces down the years have commented that I’m very cheerful and animated when I speak French.

- I remember that when I used to live in France I couldn’t really do numbers very well in French; it’s like I was saying them in my head but the ‘numbers bit’ of my brain wasn’t properly engaging.

- If I’m thinking about something terrible – like getting made redundant or making other people redundant it makes me feel really sad.

- If I consciously think about the same thing in French, there is little or no physiological effect… it’s as if the ‘pain connectors’ aren’t there; I think it, but more slowly and not sadly…

Perhaps it’s because I have to work at it. I think more slowly, and my vocabulary is less ‘fine’ in French – but it seems the pain and sadness just isn’t there when I think the same thought in French. In fact it’s not really the same ‘thought’ at all, its more a daisy chain of words which register in the mind but aren’t ‘felt’ in the same way.

So based on Keith Frankish, when bad and sad thoughts crowd in, I clearly need to switch to Frankish – or French as we know it these days. Whenever I start ruminating or feel chest clenching anxieties about work I plan to try thinking about them in French to get them under control.

Let’s see if it works… And if not there’s always Italiano! Vive la France.