Two good books came to my aid this week – ‘Fierce Conversations’ and ‘The Anatomy of Peace’.

The first argues persuasively that there isn’t a relationship you can’t improve (or set back) with your next conversation.

The thesis is that the conversation is the relationship – and you’re relationship only as good as the conversation you’re having. Stop talking and your relationship is automatically going backwards; start talking and you’re in with a shout of improving things.

The further argument is; some conversations need having – even if you really don’t want to have them. I had one like that this week.

The second book ‘Anatomy of Peace’ and the related ‘Outward Mindset’ are very simple too. But being simple doesn’t make them easy. These say that what’s happening around us (and to us) is often far more of our own making than any of us would like to recognise.

The thesis of both: is that the essence of what we create around us flows from whether we are seeing and treating people as people. Most of our problems are caused by our heart subtly and quietly hardening against people – and consequently seeing individuals and groups (even whole countries) as obstacles or vehicles.

Stop seeing the person, or start focusing more on your own needs – and we start the self-reinforcing process of pushing, shoving and self-justification.

This week I stopped pushing on the cusp of starting shoving, and had a frank and open ‘fierce conversation’ instead. An important work relationship is improved; I’m much happier and a whole slew of future problems feel suddenly more tractable – we will tackle them together not push them at each other.

Going to war with people is always easier than making peace; but the consequences rip and ripple out, and are endless either way.

Separately, coming somewhat ‘shell shocked’ from a downbeat meeting on problems with a major building project, someone kindly asked if was alright. I stopped a moment and said: “Yes, I was quiet because I was thinking.” A white lie, but partially true.

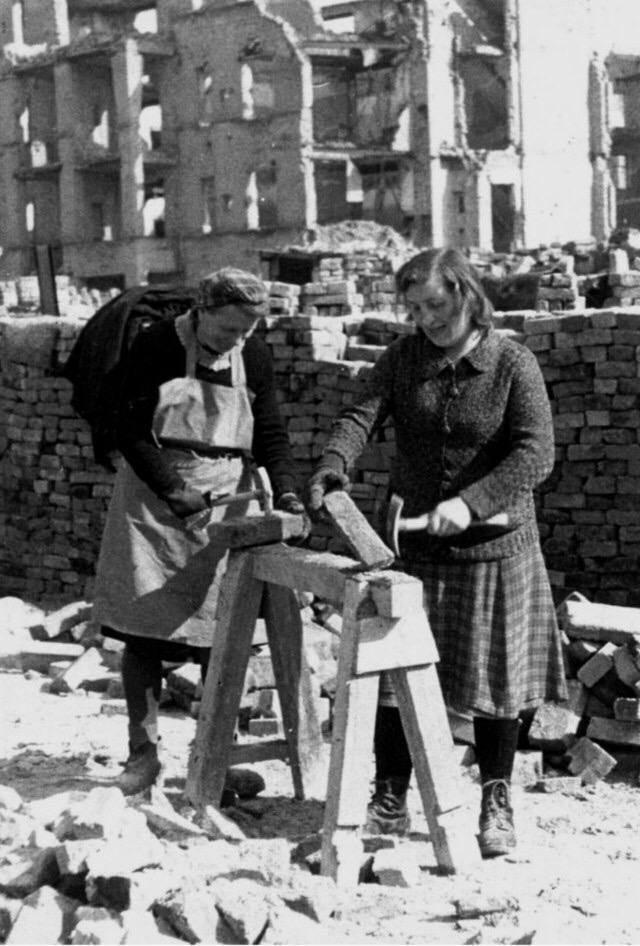

And then I mentioned the stoicism of Germany’s ‘brick women’ after WWII whom I’d read about in Neil MacGregor’s ‘Germany: Memories of a Nation’.

As Wikipedia has it, the Trümmerfrau (literally ruins woman or rubble woman) helped clear and reconstruct bombed cities where 4 million homes had been destroyed and another 4 million damaged – half of all homes – plus half of all schools and 40% of all infrastructure; they collectively tackled 400 million cubic metres of ruins.

Puts a few of my work ‘infrastructure problems’ in perspective. But it also speaks to the power of people to objectify, justify, hate, fight and destroy each other – and very often the same people to come together in a testament to the indomitable human spirit: to restore, recover, rebuild and recreate.

We have the capacity for both in us all.