I’ve started E.H. Gombrich’s ‘The Story of Art’ which was recommended by one friend and came up in conversation with another today. Gombrich says there is really no ‘Art’, only artists and what they create.

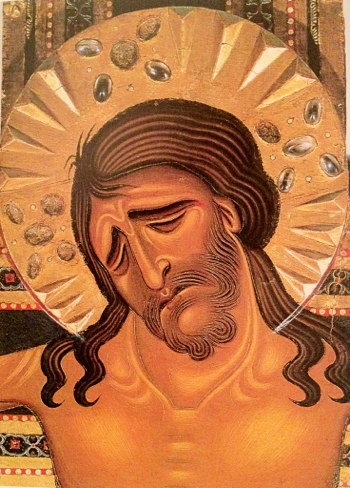

A lot of what what ‘Art’ is actually about, is nothing to do with experts, critics, audiences or patrons – it’s about the artist and their personal effort to produce something of intrinsic value. The painting above from ‘The Story of Art’ simply and powerfully captures not only the passion of Christ, but also the passion of the unknown 12th Century artist.

I pointed out today that this connects with one of my dictums for social media – if you like what you’ve done that’s good enough, don’t worry about anyone else. I think social media is largely about forgetting the ‘audience’ and simply writing or posting something you personally care about, are interested in or want to say. It then finds an audience through chance and serendipity.

At this point in our conversation today I was forced to bring in Aristotle – and we had a laugh about it. Aristotle is knockout reference once you buy into him. There’s often nothing more to say once you’ve heard what Aristotle said on a subject.

So, drawing on Aristotle’s ‘Poetics’, my definition of the job of the artist – and bloggers too, I reckon – is to forget about ‘Art’ or ‘audience’ and simply:

Say, write, paint or sculpt something transcendent and universal about the human condition in no more and no less words, notes, chisel blows or brush-strokes than are needed.

If it’s good it will find appreciation – if only from the person who matters most, the artist.